Hamiltonian mechanics

Hamiltonian mechanics is a reformulation of classical mechanics that was introduced in 1833 by Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton.

It arose from Lagrangian mechanics, a previous reformulation of classical mechanics introduced by Joseph Louis Lagrange in 1788, but can be formulated without recourse to Lagrangian mechanics using symplectic spaces (see Mathematical formalism, below). The Hamiltonian method differs from the Lagrangian method in that instead of expressing second-order differential constraints on an n-dimensional coordinate space (where n is the number of degrees of freedom of the system), it expresses first-order constraints on a 2n-dimensional phase space.[1]

As with Lagrangian mechanics, Hamilton's equations provide a new and equivalent way of looking at classical mechanics. Generally, these equations do not provide a more convenient way of solving a particular problem. Rather, they provide deeper insights into both the general structure of classical mechanics and its connection to quantum mechanics as understood through Hamiltonian mechanics, as well as its connection to other areas of science.

Simplified overview of uses

The value of the Hamiltonian is the total energy of the system being described. For a closed system, it is the sum of the kinetic and potential energy in the system. There is a set of differential equations known as the Hamilton equations which give the time evolution of the system. Hamiltonians can be used to describe such simple systems as a bouncing ball, a pendulum or an oscillating spring in which energy changes from kinetic to potential and back again over time. Hamiltonians can also be employed to model the energy of other more complex dynamic systems such as planetary orbits in celestial mechanics and also in quantum mechanics.[2]

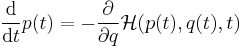

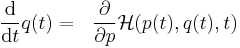

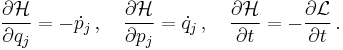

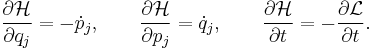

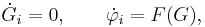

The Hamilton equations are generally written as follows:

In the above equations, the dot denotes the ordinary derivative with respect to time of the functions p = p(t) (called generalized momenta) and q = q(t) (called generalized coordinates), taking values in some vector space, and  =

=  is the so-called Hamiltonian, or (scalar valued) Hamiltonian function. Thus, more explicitly, one can equivalently write

is the so-called Hamiltonian, or (scalar valued) Hamiltonian function. Thus, more explicitly, one can equivalently write

and specify the domain of values in which the parameter t (time) varies.

For a detailed derivation of these equations from Lagrangian mechanics, see below.

Basic physical interpretation

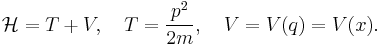

The simplest interpretation of the Hamilton equations is as follows, applying them to a one-dimensional system consisting of one particle of mass m under time-independent boundary conditions: The Hamiltonian  represents the energy of the system (provided that there are NO external forces, or additional energy added to the system), which is the sum of kinetic and potential energy, traditionally denoted T and V, respectively. Here q is the x coordinate and p is the momentum, mv. Then

represents the energy of the system (provided that there are NO external forces, or additional energy added to the system), which is the sum of kinetic and potential energy, traditionally denoted T and V, respectively. Here q is the x coordinate and p is the momentum, mv. Then

Note that T is a function of p alone, while V is a function of x (or q) alone.

Now the time-derivative of the momentum p equals the Newtonian force, and so here the first Hamilton equation means that the force on the particle equals the rate at which it loses potential energy with respect to changes in x, its location. (Force equals the negative gradient of potential energy.)

The time-derivative of q here means the velocity: the second Hamilton equation here means that the particle’s velocity equals the derivative of its kinetic energy with respect to its momentum. (Because the derivative with respect to p of p2/2m equals p/m = mv/m = v.)

Using Hamilton's equations

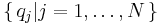

In terms of the generalized coordinates  and generalized velocities

and generalized velocities

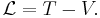

- First write out the Lagrangian

Express T and V as though you were going to use Lagrange's equation.

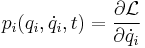

Express T and V as though you were going to use Lagrange's equation. - Calculate the momenta by differentiating the Lagrangian with respect to velocity:

.

. - Express the velocities in terms of the momenta by inverting the expressions in step (2).

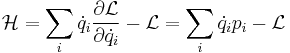

- Calculate the Hamiltonian using the usual definition of H as the Legendre transformation of L:

. Substitute for the velocities using the results in step (3).

. Substitute for the velocities using the results in step (3). - Apply Hamilton's equations.

Notes

Hamilton's equations are appealing in view of their beautiful simplicity and (slightly broken) symmetry. They have been analyzed under almost every imaginable perspective, from basic physics up to symplectic geometry. A lot is known about solutions of these equations, yet the exact general case solution of the equations of motion cannot be given explicitly for a system of more than two massive point particles. The finding of conserved quantities plays an important role in the search for solutions or information about their nature. In models with an infinite number of degrees of freedom, this is of course even more complicated. An interesting and promising area of research is the study of integrable systems, where an infinite number of independent conserved quantities can be constructed.

Deriving Hamilton's equations

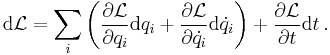

We can derive Hamilton's equations by looking at how the total differential of the Lagrangian depends on time, generalized positions  and generalized velocities

and generalized velocities  [3]

[3]

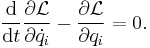

Now the generalized momenta were defined as  and Lagrange's equations tell us that

and Lagrange's equations tell us that

We can rearrange this to get

and substitute the result into the total differential of the Lagrangian

We can rewrite this as

and rearrange again to get

The term on the left-hand side is just the Hamiltonian that we have defined before, so we find that

where the second equality holds because of the definition of the total differential of  in terms of its partial derivatives. Associating terms from both sides of the equation above yields Hamilton's equations

in terms of its partial derivatives. Associating terms from both sides of the equation above yields Hamilton's equations

As a reformulation of Lagrangian mechanics

Starting with Lagrangian mechanics, the equations of motion are based on generalized coordinates

and matching generalized velocities

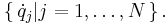

We write the Lagrangian as

with the subscripted variables understood to represent all N variables of that type. Hamiltonian mechanics aims to replace the generalized velocity variables with generalized momentum variables, also known as conjugate momenta. By doing so, it is possible to handle certain systems, such as aspects of quantum mechanics, that would otherwise be even more complicated.

For each generalized velocity, there is one corresponding conjugate momentum, defined as:

In Cartesian coordinates, the generalized momenta are precisely the physical linear momenta. In circular polar coordinates, the generalized momentum corresponding to the angular velocity is the physical angular momentum. For an arbitrary choice of generalized coordinates, it may not be possible to obtain an intuitive interpretation of the conjugate momenta.

One thing which is not too obvious in this coordinate dependent formulation is that different generalized coordinates are really nothing more than different coordinatizations of the same symplectic manifold.

The Hamiltonian is the Legendre transform of the Lagrangian:

If the transformation equations defining the generalized coordinates are independent of t, and the Lagrangian is a sum of products of functions (in the generalised coordinates) which are homogeneous of order 0, 1 or 2, then it can be shown that H is equal to the total energy E = T + V.

Each side in the definition of  produces a differential:

produces a differential:

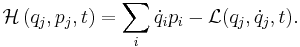

Substituting the previous definition of the conjugate momenta into this equation and matching coefficients, we obtain the equations of motion of Hamiltonian mechanics, known as the canonical equations of Hamilton:

Hamilton's equations are first-order differential equations, and thus easier to solve than Lagrange's equations, which are second-order. Hamilton's equations have another advantage over Lagrange's equations: if a system has a symmetry, such that a coordinate does not occur in the Hamiltonian, the corresponding momentum is conserved, and that coordinate can be ignored in the other equations of the set. Effectively, this reduces the problem from n coordinates to (n-1) coordinates. In the Lagrangian framework, of course the result that the corresponding momentum is conserved still follows immediately, but all the generalized velocities still occur in the Lagrangian - we still have to solve a system of equations in n coordinates.[4]

The Lagrangian and Hamiltonian approaches provide the groundwork for deeper results in the theory of classical mechanics, and for formulations of quantum mechanics.

Geometry of Hamiltonian systems

A Hamiltonian system may be understood as a fiber bundle E over time R, with the fibers Et, t ∈ R being the position space. The Lagrangian is thus a function on the jet bundle J over E; taking the fiberwise Legendre transform of the Lagrangian produces a function on the dual bundle over time whose fiber at t is the cotangent space T*Et, which comes equipped with a natural symplectic form, and this latter function is the Hamiltonian.

Generalization to quantum mechanics through Poisson bracket

Hamilton's equations above work well for classical mechanics, but not for quantum mechanics, since the differential equations discussed assume that one can specify the exact position and momentum of the particle simultaneously at any point in time. However, the equations can be further generalized to then be extended to apply to quantum mechanics as well as to classical mechanics, through the deformation of the Poisson algebra over p and q to the algebra of Moyal brackets.

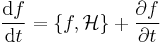

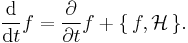

Specifically, the more general form of the Hamilton's equation reads

where f is some function of p and q, and H is the Hamiltonian. To find out the rules for evaluating a Poisson bracket without resorting to differential equations, see Lie algebra; a Poisson bracket is the name for the Lie bracket in a Poisson algebra. These Poisson brackets can then be extended to Moyal brackets comporting to an inequivalent Lie algebra, as proven by H Groenewold, and thereby describe quantum mechanical diffusion in phase space (See the uncertainty principle and Weyl quantization). This more algebraic approach not only permits ultimately extending probability distributions in phase space to Wigner quasi-probability distributions, but, at the mere Poisson bracket classical setting, also provides more power in helping analyze the relevant conserved quantities in a system.

Mathematical formalism

Any smooth real-valued function H on a symplectic manifold can be used to define a Hamiltonian system. The function H is known as the Hamiltonian or the energy function. The symplectic manifold is then called the phase space. The Hamiltonian induces a special vector field on the symplectic manifold, known as the symplectic vector field.

The symplectic vector field, also called the Hamiltonian vector field, induces a Hamiltonian flow on the manifold. The integral curves of the vector field are a one-parameter family of transformations of the manifold; the parameter of the curves is commonly called the time. The time evolution is given by symplectomorphisms. By Liouville's theorem, each symplectomorphism preserves the volume form on the phase space. The collection of symplectomorphisms induced by the Hamiltonian flow is commonly called the Hamiltonian mechanics of the Hamiltonian system.

The symplectic structure induces a Poisson bracket. The Poisson bracket gives the space of functions on the manifold the structure of a Lie algebra.

Given a function f

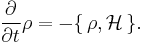

If we have a probability distribution, ρ, then (since the phase space velocity ( ) has zero divergence, and probability is conserved) its convective derivative can be shown to be zero and so

) has zero divergence, and probability is conserved) its convective derivative can be shown to be zero and so

This is called Liouville's theorem. Every smooth function G over the symplectic manifold generates a one-parameter family of symplectomorphisms and if { G, H } = 0, then G is conserved and the symplectomorphisms are symmetry transformations.

A Hamiltonian may have multiple conserved quantities Gi. If the symplectic manifold has dimension 2n and there are n functionally independent conserved quantities Gi which are in involution (i.e., { Gi, Gj } = 0), then the Hamiltonian is Liouville integrable. The Liouville–Arnol'd theorem says that locally, any Liouville integrable Hamiltonian can be transformed via a symplectomorphism in a new Hamiltonian with the conserved quantities Gi as coordinates; the new coordinates are called action-angle coordinates. The transformed Hamiltonian depends only on the Gi, and hence the equations of motion have the simple form

for some function F (Arnol'd et al., 1988). There is an entire field focusing on small deviations from integrable systems governed by the KAM theorem.

The integrability of Hamiltonian vector fields is an open question. In general, Hamiltonian systems are chaotic; concepts of measure, completeness, integrability and stability are poorly defined. At this time, the study of dynamical systems is primarily qualitative, and not a quantitative science.

Riemannian manifolds

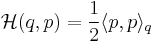

An important special case consists of those Hamiltonians that are quadratic forms, that is, Hamiltonians that can be written as

where  is a smoothly varying inner product on the fibers

is a smoothly varying inner product on the fibers  , the cotangent space to the point q in the configuration space, sometimes called a cometric. This Hamiltonian consists entirely of the kinetic term.

, the cotangent space to the point q in the configuration space, sometimes called a cometric. This Hamiltonian consists entirely of the kinetic term.

If one considers a Riemannian manifold or a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, the Riemannian metric induces a linear isomorphism between the tangent and cotangent bundles. (See Musical isomorphism). Using this isomorphism, one can define a cometric. (In coordinates, the matrix defining the cometric is the inverse of the matrix defining the metric.) The solutions to the Hamilton–Jacobi equations for this Hamiltonian are then the same as the geodesics on the manifold. In particular, the Hamiltonian flow in this case is the same thing as the geodesic flow. The existence of such solutions, and the completeness of the set of solutions, are discussed in detail in the article on geodesics. See also Geodesics as Hamiltonian flows.

Sub-Riemannian manifolds

When the cometric is degenerate, then it is not invertible. In this case, one does not have a Riemannian manifold, as one does not have a metric. However, the Hamiltonian still exists. In the case where the cometric is degenerate at every point q of the configuration space manifold Q, so that the rank of the cometric is less than the dimension of the manifold Q, one has a sub-Riemannian manifold.

The Hamiltonian in this case is known as a sub-Riemannian Hamiltonian. Every such Hamiltonian uniquely determines the cometric, and vice-versa. This implies that every sub-Riemannian manifold is uniquely determined by its sub-Riemannian Hamiltonian, and that the converse is true: every sub-Riemannian manifold has a unique sub-Riemannian Hamiltonian. The existence of sub-Riemannian geodesics is given by the Chow-Rashevskii theorem.

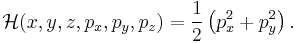

The continuous, real-valued Heisenberg group provides a simple example of a sub-Riemannian manifold. For the Heisenberg group, the Hamiltonian is given by

is not involved in the Hamiltonian.

is not involved in the Hamiltonian.

Poisson algebras

Hamiltonian systems can be generalized in various ways. Instead of simply looking at the algebra of smooth functions over a symplectic manifold, Hamiltonian mechanics can be formulated on general commutative unital real Poisson algebras. A state is a continuous linear functional on the Poisson algebra (equipped with some suitable topology) such that for any element A of the algebra, A² maps to a nonnegative real number.

A further generalization is given by Nambu dynamics.

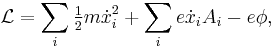

Charged particle in an electromagnetic field

A good illustration of Hamiltonian mechanics is given by the Hamiltonian of a charged particle in an electromagnetic field. In Cartesian coordinates (i.e.  ), the Lagrangian of a non-relativistic classical particle in an electromagnetic field is (in SI Units):

), the Lagrangian of a non-relativistic classical particle in an electromagnetic field is (in SI Units):

where e is the electric charge of the particle (not necessarily the electron charge),  is the electric scalar potential, and the

is the electric scalar potential, and the  are the components of the magnetic vector potential (these may be modified through a gauge transformation). This is called minimal coupling.

are the components of the magnetic vector potential (these may be modified through a gauge transformation). This is called minimal coupling.

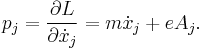

The generalized momenta may be derived by:

Rearranging, we may express the velocities in terms of the momenta, as:

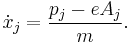

If we substitute the definition of the momenta, and the definitions of the velocities in terms of the momenta, into the definition of the Hamiltonian given above, and then simplify and rearrange, we get:

This equation is used frequently in quantum mechanics.

Relativistic charged particle in an electromagnetic field

The Lagrangian for a relativistic charged particle is given by:

Thus the particle's canonical (total) momentum is

that is, the sum of the kinetic momentum and the potential momentum.

Solving for the velocity, we get

So the Hamiltonian is

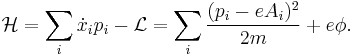

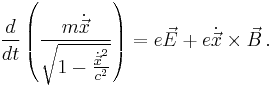

From this we get the force equation (equivalent to the Euler–Lagrange equation)

from which one can derive

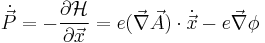

An equivalent expression for the Hamiltonian as function of the relativistic (kinetic) momentum, ![\vec{p}=\gamma m \dot{\vec{x}}[t] \,,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a4145355355cf9896501141a6a6a9b62.png) is

is

This has the advantage that  can be measured experimentally whereas

can be measured experimentally whereas  cannot. Notice that the Hamiltonian (total energy) can be viewed as the sum of the relativistic energy (kinetic+rest) ,

cannot. Notice that the Hamiltonian (total energy) can be viewed as the sum of the relativistic energy (kinetic+rest) ,  plus the potential energy,

plus the potential energy,

See also

- Canonical transformation

- Classical field theory

- Classical mechanics

- Dynamical systems theory

- Hamilton–Jacobi equation

- Lagrangian mechanics

- Maxwell's equations

- Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics)

- Quantum Hamilton's equations

- Quantum field theory

- Hamiltonian optics

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ LaValle, Steven M. (2006), "§13.4.4 Hamiltonian mechanics", Planning Algorithms, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86205-9, http://planning.cs.uiuc.edu/node707.html

- ^ "16.3 The Hamiltonian", MIT OpenCourseWare website 18.013A, http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/18/18.013a/textbook/chapter16/section03.html, retrieved February 2007

- ^ This derivation is along the lines as given in Arnol'd 1989, pp. 65–66

- ^ Goldstein, H. (2001), Classical Mechanics (3rd ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0201657023

References

- Arnol'd, V. I. (1989), Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96890-3

- Abraham, R.; Marsden, J.E. (1978), Foundations of Mechanics, London: Benjamin-Cummings, ISBN 0-8053-0102-X

- Arnol'd, V. I.; Kozlov, V. V.; Neĩshtadt, A. I. (1988), Mathematical aspects of classical and celestial mechanics, 3, Springer-Verlag

- Vinogradov, A. M.; Kupershmidt, B. A. (1981) (DjVu), The structure of Hamiltonian mechanics, London Math. Soc. Lect. Notes Ser., 60, London: Cambridge Univ. Press, http://diffiety.ac.ru/djvu/structures.djvu

External links

- Binney, James J., Classical Mechanics (lecture notes), University of Oxford, http://www-thphys.physics.ox.ac.uk/users/JamesBinney/cmech.pdf, retrieved 27 October 2010

- Tong, David, Classical Dynamics (Cambridge lecture notes), University of Cambridge, http://www.damtp.cam.ac.uk/user/tong/dynamics.html, retrieved 27 October 2010

![\mathrm{d} \mathcal{L} = \sum_i \left [ {\dot p}_i \mathrm{d} q_i %2B p_i \mathrm{d} {\dot q_i} \right] %2B \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial t}\mathrm{d}t

\,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/75b4204a9f759556f55c0af355a63854.png)

![\mathrm{d} \mathcal{L} = \sum_i \left [ {\dot p}_i \mathrm{d}q_i %2B \mathrm{d}\left ( p_i {\dot q_i} \right ) - {\dot q_i} \mathrm{d} p_i \right ] %2B \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial t}\mathrm{d}t

\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0c4be8d6c1c94a28c6a51a648a9b2e7d.png)

![\mathrm{d} \left ( \sum_i p_i {\dot q_i} - \mathcal{L} \right ) = \sum_i \left [ -{\dot p}_i \mathrm{d} q_i %2B {\dot q_i} \mathrm{d}p_i \right] - \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial t}\mathrm{d}t

\,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/902fe003bd1555893ee9c44a0059aae5.png)

![\mathrm{d} \mathcal{H} = \sum_i \left [ -{\dot p}_i \mathrm{d} q_i %2B {\dot q_i} \mathrm{d} p_i \right] - \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial t}\mathrm{d}t = \sum_i \left [ \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial q_i} \mathrm{d} q_i %2B

\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial p_i} \mathrm{d} p_i \right ] %2B \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial t}\mathrm{d}t

\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8cddf34af49f16630ea85ec57736cff9.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathrm{d}\mathcal{H} &= \sum_i \left[ \left({\partial \mathcal{H} \over \partial q_i}\right) \mathrm{d}q_i %2B \left({\partial \mathcal{H} \over \partial p_i}\right) \mathrm{d}p_i \right] %2B \left({\partial \mathcal{H} \over \partial t}\right) \mathrm{d}t\qquad\qquad\quad\quad \\ \\

&= \sum_i \left[ \dot{q}_i\, \mathrm{d}p_i %2B p_i\, \mathrm{d}\dot{q}_i - \left({\partial \mathcal{L} \over \partial q_i}\right) \mathrm{d}q_i - \left({\partial \mathcal{L} \over \partial \dot{q}_i}\right) \mathrm{d}\dot{q}_i \right] - \left({\partial \mathcal{L} \over \partial t}\right) \mathrm{d}t.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1b73578bf01577cb98e6f29c268f1d35.png)

![\mathcal{L}[t] = - m c^2 \sqrt {1 - \frac{{\dot{\vec{x}}[t]}^2}{c^2}} - e \phi [\vec{x}[t],t] %2B e \dot{\vec{x}}[t] \cdot \vec{A} [\vec{x}[t],t] \,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b39dc7cc5c76596827ab0a2c1622e8c9.png)

![\vec{P}\,[t] = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}[t]}{\partial \dot{\vec{x}}[t]} = \frac{m \dot{\vec{x}}[t]}{\sqrt {1 - \frac{{\dot{\vec{x}}[t]}^2}{c^2}}} %2B e \vec{A} [\vec{x}[t],t] \,,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3247b3479adccd52f412c7733d7cce81.png)

![\dot{\vec{x}}[t] = \frac{\vec{P}\,[t] - e \vec{A} [\vec{x}[t],t]}{\sqrt {m^2 %2B \frac{1}{c^2}{\left( \vec{P}\,[t] - e \vec{A} [\vec{x}[t],t] \right) }^2}} \,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/814c954ff50c928e7ff812ce1aa040a2.png)

![\mathcal{H}[t] = \dot{\vec{x}}[t] \cdot \vec{P}\,[t] - \mathcal{L}[t] = c \sqrt {m^2 c^2 %2B {\left( \vec{P}\,[t] - e \vec{A} [\vec{x}[t],t] \right) }^2} %2B e \phi [\vec{x}[t],t] \,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/849b65f61394913d17cdd63134475a8c.png)

![\mathcal{H}[t] = \dot{\vec{x}}[t] \cdot \vec{p}\,[t] %2B\frac{mc^2}{\gamma} %2B e \phi [\vec{x}[t],t]=\gamma mc^2%2B e \phi [\vec{x}[t],t]=E%2BV \,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8912fb7a28a6b38424dd97fd5a227556.png)